Guinea Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) Case Study

Apr 8, 2021

Amadou Traore1, Aboubacar Sidiki Cissé2, Jean Traore2, Bouna Yattassaye2, Appolinaire Lamah3, Abdoulaye Wone3, Mamadou Baldé4, Brenna Means5,6, Ileana Vélez5,6, James Banaski6, Claire J. Standley 6,‡

1 GIZ, Freetown, Sierra Leone

2 Emergency Operations Center Department, National Agency for Health Security, Conakry, Guinea

3 International Organization for Migration, Conakry, Guinea

4 World Health Organization, Conakry, Guinea

5 School of Continuing Studies, Georgetown University, Washington DC, USA

6 Center for Global Health Science and Security, Georgetown University, Washington DC, USA

‡Correspondence to Claire.standley@georgetown.edu

Key Facts

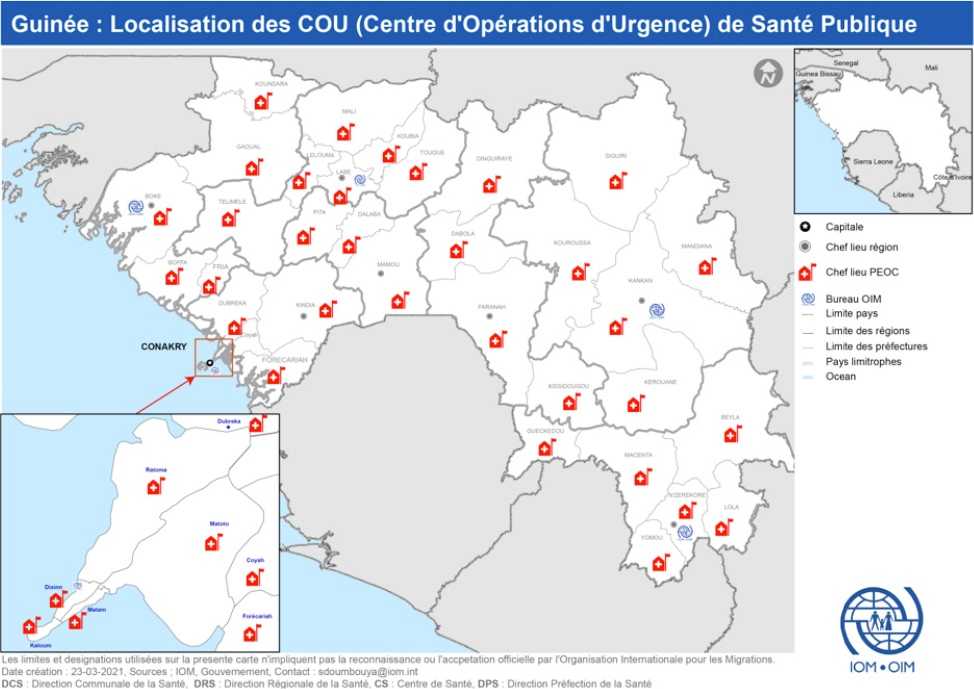

- Guinea began developing a national public health emergency management program in 2015. Since then, it has established a network of 38 public health emergency operations centers (PHEOCs), including one in every health district.

- The national PHEOC was activated to support the response to COVID-19, and plays a central coordination role in collecting, analyzing, and disseminating data, as well as operational and logistical functions. District PHEOCs are also activated in areas with reported transmission of COVID-19. The strong involvement of Law Enforcement Services (SAL in French) alongside health authorities has been a significant success in responding to this pandemic.

- The greatest challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic have been managing the increase in the volume of work, and adequately addressing surge staffing with minimal resources.

- Establishing more robust emergency response funding mechanisms; additional and task-specific training for surge personnel; and updating medical countermeasures and supply chain management plans are priority future actions.

- PHEOC personnel would benefit from the availability of self-directed training resources, particularly in modular formats, as well as routine one-on-one mentoring in specific areas such as table-top exercises and reviewing SOPs, and/or targeted technical assistance following continuous evaluation of each PHEOC.

Map of public health emergency operation centers (PHEOC) in all 38 health districts in Guinea as well as at the national level, forming the national public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) network. Translations: Capitale = capital; Chef lieu region = Regional capital; Chef lieu PHEOC = PHEOC site; Bureau OIM = IOM office; Limite pays = country border; Limite des régions = regional border; Limite des préfectures = prefectural border; Pays limitrophes = neighboring countries. [Credit: IOM]

Establishment and Operation of the PHEOC network

Guinea’s Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) is a department within the National Agency for Health Security (Agence National de Sécurité Sanitaire, or ANSS), a public health agency operating with financial and administrative autonomy under the Ministry of Health. It has a recognized legal mandate to perform emergency response functions, warranted by both the presidential decree that created the ANSS in 2016 and the Ministerial ruling that attributed the functions of each of its five departments, one of which includes the EOC.1

There is a national PHEOC, situated in the capital city, Conakry, as well as subnational PHEOC capabilities in all 33 health districts, established with minimal infrastructure. The PHEOCs at this level are housed at the District Health Directorate (Direction Préfectorale de Santé, or DPS) and function under the leadership of the district health director. In Conakry, which is composed of five municipalities (communes), a PHEOC is represented in each under the authority of the Commune Health Directorate.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of activities were carried out at the national and subnational levels to ensure operationality of the PHEOCs, with the ANSS working in collaboration with bilateral and multilateral partners. Starting in 2015, partners such as WHO, IOM and USAID/OFDA provided assistance to equip PHEOCs with minimum infrastructure and equipment, including conference rooms, tables, chairs, computer screens, office supply and internet (unfortunately, connectivity support at the district level has been discontinued).

With support from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), documents were developed at all levels, but particularly the national, including a generic Emergency Response Plan, Concept of Operations and SOPs, plus an Emergency Response Management Organogram. A vulnerability and risk analysis & mapping (VRAM) effort was also conducted with technical assistance from WHO to facilitate the development of an all-hazard emergency response plan (not yet developed).

The development of plans and procedures was preceded by the training of national-level PHEOC personnel in Canada (in collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada, PHAC) and/or in the United States, hosted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC); training was “cascaded” to subnational level through a training of trainers initiative implemented by the ANSS with support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Georgetown University. All districts have participated in at least one table-top exercise. A full-scale simulation exercise was carried out in 2019 in Conakry and the District of Forecariah, and an After Action Review was conducted, including a report. The continuous improvement plan has yet to be actioned. Other partners, such as the UN’s Multi-Trust Partner Fund, Expertise France, and GIZ have also provided support to strengthening Guinea’s public health emergency management capacities. The PHEOC staff drew from numerous documents, training manuals, and other resource materials produced by WHO, PHAC, US CDC and others to guide development and operationalization of the PHEOC network. For the past two years, IOM has also set up a mentorship program for six PHEOCs in Lower Guinea (Boke, Forecariah, Coyah, Dubreka, Fria and Kindia) which allowed for an operational model with an optimal level of functionality in these high-risk zones.

Support to the COVID-19 response

The national PHEOC was activated to support the Guinean COVID-19 response, specifically in order to serve in a coordinating role, as described in its plans and procedures. Its primary tasks include collecting and compiling National Situation Reports; analyzing, sharing, and supporting decision-making from individual district and commune PHEOCs; and providing documentary support to various technical commissions. Other activities include assisting in the planning and managing of meetings and press conferences (in coordination with the communication department of the ANSS), contributing to the draft meeting reports, and following through with recommendations from various meetings. In each district with confirmed active transmission of COVID-19, the district PHEOC is activated, and a regular situation report produced and shared with the national level.

As part of the response to COVID-19, thanks to engagement from IOM, with the support of the US and Canadian governments, the seven PHEOCs in the area known as Greater Conakry (the communes of Matoto, Kaloum, Dixinn, Matam and Ratoma, plus the districts of Coyah and Dubreka) have benefitted from significant material support, such as video conference equipment, allowing for interconnection with the national PHEOC. In addition, this experience enabled the Incident Management System (IMS) to be triggered in each of the PHEOCs. This supported the strengthening of multisectoral coordination, and particularly the involvement of the Law Enforcement Services alongside health authorities. The greatest challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic have been managing the increase in the volume of work, and the need to adequately address surge staffing with minimal resources. Although the response has been generally well-managed using established emergency management structures, full application of the documented procedures, for instance following strict incident management system processes in terms of EOC activation and de-escalation for the response, has been challenging with lack of full understanding and adherence to the PHEOC standards and modes of operations.

A number of activities have been conducted during the pandemic to assist PHEOCs at the national and subnational levels to adjust and/or expand their capabilities. These included in-person training in-country, participation in training outside the country, mid-term exams, deployment of additional personnel, cross-sector collaborations, and international collaboration and coordination. In addition, some partners, notably IOM, WHO and AFENET have provided direct technical assistance in terms of deployment of support personnel.

In addition to COVID-19, resources and coordination have been further stretched by the need to respond simultaneously to multiple infectious disease outbreaks. During 20202021, the PHEOC has had to oversee responses for four further high priority infectious disease outbreaks, including yellow fever, vaccine-derived polio virus, measles, and more recently, a cluster of Ebola virus disease cases in N’Zérékoré, not far from the epicenter of the devastating 2014 epidemic. These multiple responses have placed even greater strain on the PHEOC’s management systems, with one potential recommendation being to establish a management committee or IMS with a separate incident manager for each outbreak, to help avoid overburdening individuals and ensure more effective oversight. More generally, the pandemic has affected continuity of services for other public health programs, including the coordination of mass immunization campaigns by district PHEOCs. The coordination efforts of the national PHEOC remain focused on COVID-19 and as such there is limited capability to maintain vigilance on other diseases under surveillance. Continuity of essential services is proving to be a challenge during the pandemic, although acknowledgement of the situation has been made, with some efforts to ensure renewed attention is paid to other health issues.

Future Opportunities

While Guinea has made significant strides in establishing and operationalizing its national PHEOC network in the past five years, there remain some areas that would benefit from further strengthening, including emergency response funding; surge staffing for specific response components like active surveillance, contact tracing, and case management; and additional case management facilities for a rapidly spreading or acute epidemic situation in the future. Improvements could also be made to processes and procedures for procuring medical countermeasures, and for overall supply chain management during an emergency. These gaps are in line with the recommendations derived from Guinea’s Joint External Evaluation, conducted in 2017.2

Identification of alternative funding mechanisms to establish contingency resources well before a future public health threat will be important. These efforts are already underway, with support from IOM and other partners helping to advocate for mobilization of local resources (private companies, multinationals, local authorities, etc.) as well as international funding. In this way, the establishment of a decentralized response fund, equipped with a flexible disbursement mechanism and a powerful accountability system, should make it possible to strengthen capacities for local and rapid management of public health events. Other tools and activities, such as additional human resources training and prepositioning of personnel; including surge staff training in all areas of the response mechanism; identification of additional/surge case management facilities well ahead of future emergencies; and the revision and exercise of the medical countermeasures plan should also be considered to strengthen Guinea’s public health emergency management systems and enable more effective future responses.

Self-directed, online learning materials for PHEOC staff, as well as the scale-up of IOM’s mentorship program, would be helpful to sustain and refresh knowledge and understanding. The most useful formulation would be to create modular trainings specific to particular response components, to provide directed and focused information on key areas where skills are needed. Examples of potential response training modules could include response coordination, risk assessment and monitoring, surge staffing, case management protocols, medical countermeasures and logistics management, and infection prevention and control. Separately, and also to bolster the impacts of self-directed learning, continued targeted technical assistance based on specific needs would also be helpful, to include refresher trainings, simulation exercises, and development or review of simple and schematic SOPs.

Endnotes

- Attal-Juncqua A et al., 2019. Legislative assessments as a tool for strengthening health security capacity: the example of Guinea post-2014 Ebola outbreak. Journal of Global Health Reports 3: https://doi.org/10.29392/joghr.3.e2019060

- WHO, 2017. Evaluation externe conjointe des principales capacités RSI de la République de Guinée. Rapport de mission : 23-28 avril, 2017. Geneva, World Health Organization. Licence : CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.